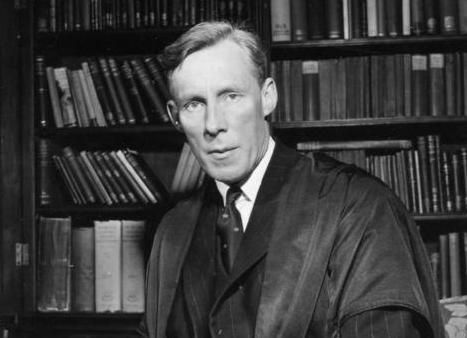

"Some Reflections on the Game of Eton Fives" by Jack Peterson

Jack Peterson is one of the legendary names in the history of Eton Fives. He was captain of Fives at Shrewsbury and Oxford, a Master at Eton then Headmaster at Shrewsbury, three times a Kinnaird Cup winner and Chairman of the EFA immediately after the Second World War. He produced a booklet called "Some Reflections on the Game of Eton Fives" and Old Salopian and member of the Marlborough Fives Club Peter Westwood has transcribed the booklet into electronic form from the copy in Shrewsbury School Library:

SOME REFLECTIONS on the game of ETON FIVES by J. M. PETERSON

PREFACE

The advice offered in the following pages is addressed chiefly to the player who has already achieved a certain degree of competence. The needs of the beginner are not entirely ignored, and it may be hoped that he can derive some benefit from envisaging certain strokes, even if at first he lacks the skill to execute them. By and large, however, the only advice that can be given to the beginner is ‘Play as much as possible, preferably with players better than yourself’. This may seem somewhat unhelpful, but the beginner need not fear that he will not make continuous progress from the moment that he starts to play.

A general word of warning is perhaps needed. In the text certain tactics are, inevitably, mentioned as normal, but one of the chief aims of the book would be lost, if the adoption of the principles laid down led to a stereotyped form of play. Fives is played with the hand, but even more with the head. The good player will master all the strokes, and vary his tactics to the needs of the moment.

Finally, I hope that what is here written will encourage the members of my old School to take up one of the best of ball games, which “men go on playing for the rest of their lives”. I hope too that they may find as much enjoyment in playing the games as I have done.

J.M.P.

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS

A good Eton Fives player must be light on his feet, keen of sight, and at least moderately supple in the wrist. The rest is practice. No one however naturally gifted can hope to become really proficient at the game without long and constant practice, though the task is considerably lightened for those who are truly ambidextrous. Some considerable time must elapse before the beginner can find his way about the Court, gauge the angle of the shot off the front wall, and familiarise himself with the various ledges and protuberances, especially around the Buttress. From the very start the chief task for a beginner must be the gradual strengthening of the left hand. For owing to the fact that the Buttress is on the left hand side of the Court—a fact which is due to the position of the North Porch in Eton College Chapel—Fives is pre-eminently a left-handed game. It is not uncommon to see a left-handed player manoeuvring, often awkwardly, so as to take every shot with this hand. That this should be possible at all proves that the left-hander can make shift with tolerable success without using the right hand; but at the same time such awkward tactics reveal the need for real ambidexterity. The left-handed player undoubtedly has a big initial advantage, but he too must strengthen his other hand, if he is ever to hold his own in good company.

EQUIPMENT

A word or two first about equipment. Shoes should be as light as possible. The ordinary cheap gym shoe I have found as good as anything. I do not recommend the heavier buck-skin type with thick sole: it does not bend easily across the ball of the foot, and the sole though it wears well tends to become slippery.

Gloves when new usually have too much padding. What is required is a close fit with enough padding to avoid bruising: many players wear a thin pair of ‘inners’. New gloves are always stiff and clumsy, and some time must elapse before they become moulded to the hand. A rubber band over the wrist helps to prevent fingers slipping inside the glove. In this connection a few observations on the subject of bruising may not be out of place. A really bad bruise may keep you out of the game for a month, and even a slight one will blunt the edge of your play and quite destroy your enjoyment of the game; and so it is as well to take what preventative measures one can. Most bruises are caused by hitting too hard when the hands and fingers are cold. It is advisable on cold days to warm the gloves and soak one’s hands in hot water before setting out for the court. In any case never hit hard until the hands are thoroughly warm. For minor bruises I have found plasticine very useful: it absorbs the shock of the stroke very well, and it is not bulky, but I cannot say that is very easy to put on.

Before we discuss the tactics of the game there are two other subjects which deserve more consideration than they usually receive, namely,

SERVING AND LETS

On the whole the standard of serving is very low. Indeed it may be said to be the most effective part of some people’s game, for they serve so badly that it is almost impossible for their opponent to produce a difficult slam. This is not playing the game: your opponent is entitled to the best serve you can give him. In most cases what he will like is a serve that bounces as high as possible fairly near the top step, and a little to the right of an imaginary line running down the middle of the court. This is, it must be admitted, not easy to do, but the method to be adopted is at any rate clear enough: the Server must come out of the Buttress and stand near the middle of the court just on the top step. He must then contrive to throw the ball in such a way that it bounces as high as possible against the side wall having hit the front wall first. The height of the bounce off the floor depends on the height of the drop off the side wall. A serve which hits the side wall only half way up will not be a good one, however high it first hit the front wall. When serving to a left-hander throw the ball up more into the angle of the wall so that it bounces further out into the middle of the court. There is always plenty of time to take up one’s position again to receive the Slam.

LETS

Most lets are due to clumsy play: the better the players, the fewer the lets. But even in the best games there are bound to be occasions when a let should be conceded. You should offer your opponent a let, if you have baulked him or prevented him from having his best chance to counter your stroke. He is not bound to accept it. It should be remembered, however, that if a player attempting to take a ball in circumstances in which a let might have been granted gets it up, he must abide by that shot even if it subsequently goes out. (See rule.) Be generous in offering your opponent a let; be very strict with yourself in accepting one. Remember that the standard to be applied is the standard of your own play. You have no right to claim a let, because it is just conceivable that the best player you have ever seen might perhaps have got it up when at the top of his form. More than this; you must apply the standard of your game with due regard to your energy at that particular moment. You must not accept a let, because if you had been standing on the other leg you might have got it; or because if you had been attending you obviously would have got it; or just because your opponent offers it.

While on this subject one must point out that the two players who are on the top step must allow an opponent in the back of the court to have an unrestricted shot. They must not stand upright so that he can return the ball only too high or to a different part of the court. These remarks apply particularly to the player who is striving to maintain a tactical position over the Box. Such a player should stoop to allow his opponent, particularly if he is in the left of the court, the lowest possible return. I stress this point, because it is a very prevalent fault. It is not a sufficient answer to say, “O well, he can always hit me in the back and claim a let!”

THE GAME

Let us now consider how a point may be won. We must be quite clear in our minds both as to what we want to do, and how we are going to do it. Apart from mistakes made by one’s opponents (and we must not rest content with so passive an attitude as this implies), a point is won (a) by ‘killing’ or ‘nicking’ the ball. A ball that is killed or nicked (and the two terms are synonymous) is one which rebounds off the front wall in such a way that it either goes into the box and stays there, or hits the angle formed by the floor and the walls either of the buttress or the court at large. A ball thus hit runs along the ground and cannot be got up. Secondly (b) a point is won by hitting one’s opponent full toss off the front wall; and thirdly (c) by putting the ball out of his reach, or beating him by the pace of the stroke. As the line on the front wall above which the ball must be returned is quite high, and as the buttress is only a few feet away from the front wall, it is obvious that only a ball that is hit downwards will have a chance of nicking in the buttress. This fact explains why most points are won off volleys hit about the level of the head or a little higher. Hence the great importance of volleying in the game; hence too the need for ‘cut’ (about which much more will be said later), and the necessity for not hitting the ordinary ground shot too hard. As regards this last shot it will be obvious that a ball, which is hit hard from below or about the level of the line is certain to rebound onto the buttress quite high up. Such a stroke will not embarrass a reasonably agile opponent. These basic facts should be borne in mind in what follows.

THE SLAM, CUT AND SPIN

The slam is of supreme importance, for your opponents cannot score at all unless they can get it up. Nothing is more demoralising to a side than repeated failure to take slams. The rallies when your opponents are up may be long and even, but unless you can master their slams, the score will eventually be 0-12 against you. It is therefore of the highest importance to be able to produce a really difficult slam. Most people rely too much on mere ferocity of stroke. Speed may be disconcerting at first, but a good player will soon take slams of this crude type, however fast they are hit, and he will usually take them easily. It is worth mentioning too that a player who hits each slam as hard as he can expends a great deal of energy which he may long for in vain in the fifth game; and he is very likely too to hit a fair number out of court off the ledge. The most difficult slam to take is undoubtedly one which pitches close to the feet of the server as he stands in the corner of the buttress. With a serve that bounces to the normal height this can only be achieved if the ball is hit with ‘cut’.

As this ‘cut’ is of great importance in the game we must here digress to explain its meaning. Most people will realise instinctively what is meant, and will probably also see how to achieve it, but in case of doubt an attempt must be made at a fuller explanation. Anybody who cares to make a few experiments with a tennis ball and a racquet against a wall will soon see what is meant. If the ball is hit with an absolutely ‘flat’ racquet (i.e. one held parallel to the front wall throughout the stroke) the ball will rebound at the angle corresponding to impact. This happens in Fives when the player hits with a stiff wrist and a ‘round-arm’ action. If the ball is hit with ‘top spin’ i.e. if the strings of the racquet are drawn up and over the ball as it is hit, then it will rebound upwards off the wall. It is difficult to impart such a spin with the hand and the attempt to do so at Fives would be suicidal, for it would increase the chance of a volley. ‘Cut’ is the opposite of this ‘top spin’, and is achieved by drawing the strings of the racquet down and under the ball. The method is similar in Fives: the ball must be hit with a flexed wrist, and the fingers and glove must be drawn smartly downwards as the stroke is made. A ball hit thus dips quickly off the front wall, and therefore hits the ground nearer the front wall.

We are now in a position to apply what has been said to the slam. It will be obvious that a slam hit with a stiff wrist and no ‘cut’ will either be exceedingly slow or reach the server at the most convenient height, somewhere between the knee and the thigh. By hitting with ‘cut’ we can hit faster and at the same time make the ball bounce sooner. Moreover it is likely to swerve slightly off the front wall, and its pace off the ground is accelerated. Such a slam is for all these reasons not easy to take: an opponent may miss it altogether, and even if he succeeds in getting it up, he is bound to return it upwards and in so doing may give an easy volley. It is not easy to hit this slam really hard: most people in achieving pace lose spin. The spin is more important than the speed. I have described this slam at some length, because for reasons which I will now repeat it seems to me to be the best standard type to adopt: (a) it is hard to take (b) it may lead to an easy volley and (c) it does not demand a great expenditure of energy.

But there are many other types of slam which may be briefly summarised. First, the shot straight down the side wall. For this slam you require, ideally, a serve which bounces fairly near the side wall. It must be hit hard and low, and in its flight into the lower court should hug the right hand side wall as near as possible without hitting it. Secondly, the slam down the middle of the court diagonally from corner to corner. This slam is common with left-handers, and may occur inadvertently with right-handers when the walls are wet. In normal conditions the right-hander who wishes to bring off this slam must hit the ball with some side spin as well as cut; he must hit the right side wall first very close to the corner. The slam which hits the front wall first before the side wall is very easy to take. Thirdly, the slam round all three walls on the top step. This slam is usually taken by the Server’s partner. It is therefore a good one to use when he is lying too far back, but it is seldom a winner, and should be sparingly employed. You should aim to make the ball bounce low on the left wall a foot or two in front of the buttress. Finally, a drop shot hit very gently against the front wall aimed if possible so as to hit the edge of the horizontal ledge on the right wall. This slam too should not be overdone; but it may be effective in one of several ways. If it does hit the edge it may be an outright winner; or both your opponents may rush for it and muddle each other; or, finally, the server’s partner may give you a volley off his return. There are, of course, many variations of these four main types of slam. The good player will master them all and employ them with discretion.

At the beginning of a game start off with your most effective slam; if that is successful, stick to it. Never change winning tactics! If on the other hand your opponent gets it up easily, try him with something else. Fives is a game which is played with the head no less than with the hand, so try to find out the weak spots in your opponents’ play. Do not forget that a mere change of pace is often effective. So many people hit every slam and indeed every shot in exactly the same way and at the same pace. They are easy prey.

TAKING THE SLAM

Everybody has his own methods for doing this and no definite position either can or should be laid down. As a general rule, however, I advise beginners at least to try taking up a crouching position right inside the angle of the Buttress. Here you have the longest possible time to sight the ball in the opposite corner; you have the best chance of leaving to your partner the slam that goes round all three walls; and the ordinary slam that is hit without much cut will come readily to hand. If, however, this position does not commend itself to you, try standing a little further out. It is possible also to retire under the wall (opposite the box) after serving, and hope to retrieve the ball as it rebounds off the buttress. In a bad light and against a ferocious hitter this may be the only thing to do; but it is in the nature of a policy of despair, and should only be resorted to in moments of crisis. It leaves the box quite unguarded, and a good player will often hole out there, if he has the sense to alter his slam accordingly. On the other hand, if he goes on banging away, you will get a fair number up.

Personally I always watch my opponent actually hit his slam before transferring my gaze to the corner. I find it easier in this way to gauge the pace and angle of the shot. But there are players who watch the corner all the time.

When the walls are wet and slippery (which happens in many courts when there has been a sudden rise in temperature) the slam is apt to come back very fast and at an acute angle down the middle of the court. Your partner will have to take most of these shots, but you can sometimes help him by standing over the box or even further to the right. In any case as soon as you have got the ball up be sure to come out from the angle of the buttress; do so likewise when you leave the slam to your partner, for you want to give him a chance to nick the ball with his return. In returning a slam it is often not possible to do more than just get it up. Be careful not to give a volley to your opponent who will very likely spring up on the top step close to the wall in anticipation of such a chance. The safest place to return the ball is near the left hand corner, as low as possible of course.

THE RALLY

It should be realised that the Server and the player who is hitting the slam are always the protagonists in the game. It is rare for a player in the Lower Court to have many chances of scoring a point outright—unless one’s opponent is so obliging as to crouch under the wall all the time, and even then the shot must be very accurate if it is to nick the buttress or come to rest in the box. The players in the Lower Court should therefore concentrate first and foremost on getting everything back, and secondly on never giving away a volley. The ball must be returned as low as possible, and it will seldom pay to hit it very hard.

SOME GAMBITS ON THE TOP STEP

It will be obvious from what has been said before that winners cannot be scored at will from any part of the court, and off any and every shot. Much of the time in a rally is taken up in manoeuvring for position, and in trying to induce one’s opponent to offer one a volley. Once more it must be emphasised that the volley is the ‘killing’ stroke par excellence, for even when, as often happens, it is not actually nicked or hit into the box its speed is often too much for an opponent. It can be hit very hard, because of course it is always hit downwards and there is consequently little chance of its going out.

(a) One of the simplest gambits when playing on the top step is to return the ball high over the buttress so that it bounces right at the back of the court close to the left hand wall. A weak player will find some difficulty in returning this at all, and even if he gets it up he is very likely to hit the ball high round the left hand corner hitting the side wall first. In this case a quick-footed opponent should be able to take it on the volley off the front wall, if he starts as he should with his foot on the step near the middle of the court. Of course your opponent in the back of the court, if he is a good player, may very likely volley your original stroke over the buttress; in this case it is wisest to abandon this gambit.

(b) A good many chances to volley occur in every game near the front wall in the left hand corner. It is here that a player with a strong left hand scores most heavily. Such volleys can be dealt with in two ways. First, they can be hit hard and fast so as to nick the bottom of the buttress. Good wrist work is essential for this stroke, and accurate “length” is even more important than speed. Secondly, they can be hit across the body and diagonally down the court towards the right hand corner by the bottom step. This shot is effective only if it is hit very hard indeed, and much practice is needed for those who are not naturally left-handed. The player in the Back court is often taken by surprise by this shot. A judicious mixture of two such dissimilar strokes will be found very profitable.

(c) Fiddling. By this term I mean the policy of just returning the ball above the line when playing within a foot or two of the wall. I use the term because I think the constant adoption of such a form of play is fiddling. But it has its uses: in a long rally it will enable you to slow down the pace and regain your breath, and apart from these defensive considerations you may very well give a nervous opponent an attack of the ‘jitters’, so that he will either fail to get the ball up at all, or in doing so will give you a tasty volley. It is of course possible that you may be the victim yourself! In any case remember that the ball must be hit with a distinct stroke of the hand or wrist; it must not be lifted or carried. When ‘fiddling’ in the corners aim for the edge of the lower of the two ledges: if you can hit this you will often win the point outright.

(d) Often a ball returned from the back of the court is hit too high or too hard, so that it rebounds off the front wall onto the higher of the two sloping faces on the buttress i.e. the one which slopes away from the front wall. In this case the ball bounces up nearly vertically, and a player standing by the box is presented with a volley to his left hand. It should be possible to kill this volley, and yet one seldom sees it done. I think the reason is that the player is often very awkwardly placed on his feet, and also has to play the stroke across his body from left to right. All that is required is a good length shot, but in such circumstances accuracy is difficult to attain.

(e) If you are presented with a volley to your right hand when you are standing in the centre of the top step, a very hard shot down the right hand wall to the back of the court will often score a point. In general most players do not make enough of this opportunity.

‘LENGTH’

Length is so important that it requires a separate paragraph for its consideration. The simplest illustration will be provided by a shot into the box: a ball hit with poor length will either bounce short or hit the buttress above, but a ball hit with the correct length will go straight in. It will be obvious therefore that length is obtained by a combination of speed and height off the front wall. One of the reasons why the volley is such an effective stroke is that the hand being high above the line at the moment of hitting the ball can be hit straight downwards in what is more or less a flat trajectory. On the other hand the ball which bounces off the floor lower than the line must be ‘lobbed’ into the box with a flight that first rises and then falls. Assume for the moment that you are presented with a straightforward chance to find the box in the latter circumstances. Your opponent is crouching under the wall; you are standing just below the step a little to the right of the centre of the court; and the ball bounces easily to your right hand on the top step in front of you. Judge the height and the angle carefully, and then do not hit too hard! I emphasise this as much as possible, because one so often sees quite competent players blazing away from this position, and the ball subsequently bouncing harmlessly off the buttress towards the man under the wall. Of course, a good player will probably not be under the wall, and you may be mortified to see your exquisite stroke neatly volleyed out of the box just as it was going in. When this happens you are beginning to play in the best company. I shall suggest a method of overcoming this last difficulty later on in the section entitled ‘More about Cut’.

HITTING ONE’S OPPONENT WITH THE BALL

In the writer’s opinion not enough points are won in this way by the generality of players. Speed of foot is essential, and you must be careful to disguise your intention as much as possible. The best chance comes when your opponent is under the wall or just emerging from that position. If you do not feel sure of killing the ball in the normal way (and every player has days when he seems quite unable to get a length) try a drop shot onto your opponents head, or puzzle him more by playing the stroke off the side wall first. In the latter case remember to play the shot which will come onto him from behind his back. These shots should usually be played off a volley, not because they are impossible off the ground, but because off the ground they are more easily anticipated. Surprise is the chief factor in success, so do not overdo it.

TACTICS

On the top step you will score most of your points in or around the box, but do not forget that an occasional very hard shot to the back of the court, aimed diagonally towards the ‘bricks’, may catch your opponent napping—particularly if out of the corner of your eye, or from the evidence of your ears, you are aware of his edging up towards the buttress! Another telling stroke can be made if you are standing by the box and the ball bounces fairly high to your right hand. Hit this underhand quite hard, high enough on the front wall to ensure that the ball just skims over the buttress and bounces as near as possible to the back of the court.

In general on the top step strive always to take and keep the initiative. Hustle your opponents all you can! Vary your tactics and keep them guessing! If you can score five or six quick points in a single hand, you may quite demoralise a lily-livered partnership. There will be times of course when you must go under the wall; but always realise that this position is a purely defensive one and dangerous against a good player, so try to get back onto the step as soon as you can. If you give your opponent an easy volley, rush under the wall (on the left hand side, of course) and hope for the best! If there is not time for that, don’t despair! Crouch right down and watch the front wall. You will find sometimes to your surprise that you can get it up. It has already been said that the player on the top step is the spear head of the attack. He should therefore take everything he can, including volleys just behind the buttress or below the step. He should always take everything that bounces on the top step, unless he shouts to his partner to relieve him. Moderate players, however, would be well advised to leave the more difficult volleys to their partners in the back court. Take everything on the volley that you possibly can. If you let the ball bounce, you will probably lose just that fraction of a second when your opponent was off his balance or on the wrong foot. Always be thinking hard what your opponent is going to do next: most players have their favourite shots, and some always play the same shot, and very often if you see it coming you can make a quick and unexpected reply.

In the lower court. Remember that when you are playing in the Lower Court your task is primarily a defensive one. You will seldom, in good company at any rate, have a chance of killing the ball off a volley, except perhaps over the buttress; and no one would say that that is an easy shot. It will be obvious from what has been said in the previous section on the subject of ‘length’ that it is very difficult indeed to nick the ball or hit it into the box from the back of the court. Whenever possible cut the ball down as much as you can; if the bounce is too low to admit of this, return the ball as low as possible and not too hard. Against a good player a hard return will often result in a volley. It will seldom pay you to hit the side wall first; one exception to this rule will be mentioned later. Unless you are deliberately hitting into the back of the court, you should normally return the ball into the buttress as low as possible.

When you have to take a ball at the back of the court on the left hand side behind the buttress, you must be very careful not to give a volley to the man on the top step. There are two possibilities for you: either lob the ball back so that it just and only just reaches the front wall above the line, or lob it right back over the buttress again, and see what your opponent makes of the same shot. A third alternative which is always safe is to hit the ball left-handed round the right hand corner in the manner of a slam. The objection to this last alternative is that the players on the top step are likely to be in the way and a let results.

When your partner is up, you must be very much on the alert, ready to take the slam which is hit straight down the side wall, and also on the look out for the one that goes round all three walls. If this latter is well hit, the second bounce will be quite near the middle of the step, and if you are hanging too far back you may fail to get there in time. When the walls are damp, the slam is likely to come back very fast at an acute angle down and across the middle of the court. These slams are difficult to return, unless you are fairly sound with the left hand and manage to get to them before they hit the left hand wall. Stand more in the centre of the court.

Nearly always try to return the ball into the buttress from the back of the court, even if you know you cannot nick it. Once more remember to hit as low on the front wall as possible and not too hard. The average player does not take nearly enough trouble to aim from the back of the court being content to return the ball almost anywhere against the front wall. As long as you keep the ball low you are quite likely to hit one of the many edges around the buttress, and even if you do not succeed in doing this, you will enable your partner to come out from under the wall, should he have been forced there by the previous stroke.

We must now mention the stroke referred to in the first paragraph of this section as an exception to the general rule that the return from the Lower Court should always hit the front wall first. This stroke can be made from almost any position in the right hand half of the Lower Court, but it is most easily executed from a spot a little further down the court from where a normal serve bounces. It is hit right-handed like an ordinary slam but without any cut in such a way as to bounce in the box or nick the bottom of the buttress. It is really a very simple stroke, and a little practice will soon give you the feel of the shot. If your opponent on the top step is under the wall or on the right hand side of the top step, it will almost certainly be a winner. Even if he is standing by the box, you may sometimes win the point by nicking the ball in the buttress. A useful variant from this position is to hit the ball very hard down the right hand wall, especially if you have reason to think that your opponent in the back of the court is standing too far up, as he often is. But you must not hit the side wall as well.

During the rally if your partner is under the wall, and you see your opponent taking deliberate but careful aim for the box, creep up quietly and be ready to volley it out. I say ‘creep up quietly’, for if he hears you coming he will probably hit it down the side wall, and you will be left stranded.

A good player will often score points by hitting the ball diagonally to the back of the court, aiming, ideally, at the ‘Bricks’, both right-handed to the left hand side and vice versa. These strokes, however, are not easy for they must be hit both hard and low. Even those players who have the necessary skill should not indulge in the shot too much, for they may be intercepted by a good volleyer.

As a general rule, and whenever you are in difficulties, play for safety from the back of the court: return the ball as low as possible and not too hard. When your partner is ‘slamming’, be on the alert to stop or touch the ones that he hits out. If you have to jump to do this, you must land with both feet in the court, or the foot that first touches the ground must do so inside the court.

GAME BALL

Remember when you are serving that you may not move both feet onto the top step until after the ball is hit. Personally I like to step back after I have thrown the ball up, and move forward as the ball is hit. In this way I can see how and where my opponent is hitting the slam, and I am already on the move if, as is likely, I have to make a dash for the front wall. By stooping low at the same time I may sometimes pick up a volley.

I shall not here enter into the Game Ball controversy, but I would like to ask those who are discontented with the present rule to consider whether they are absolutely certain of killing the Game Ball slam? I do not myself think that it is at all an easy thing to do. It must be realised that length is everything in this particular shot. Against a good player you must hit fairly hard, or he will volley your shot easily; and if you are to hit fairly hard you must impart a lot of cut to the ball to bring it down sharply into the box or buttress. The ideal slam at Game Ball is one that nicks in the very corner of the buttress. One that hits the left side wall low just in front of the buttress and then off the buttress runs away very quickly towards the right hand corner is also nearly impossible to take. At all costs you must restrain the tendency to hit too hard: a hard shot is very likely to give an easy return off the front wall having first rebounded off the buttress. There is always too the danger of hitting the ledge on the line, and of losing the game by the ball subsequently hitting the roof. I do not advise any other type of slam at Game Ball. A very strong left-hander might perhaps score with a hard return towards the ‘bricks’ on the right hand side of the court. The Game Ball cut is very important, so do not accept an indifferent serve at this point.

MORE ABOUT ‘CUT’

The effect of ‘cut’ has already been explained, but hitherto we have only mentioned the natural cut obtained by drawing the hand down smartly over the ball from top to bottom. Naturally this stroke can be made only off a volley or off a ball that bounces rather high. It is possible, however, to impart the same spin to the ball when playing as one might say ‘under-hand’. To do this the hand must be held flat, parallel to the ground with the palm upper-most. Then as the ball is hit the hand must be shot smartly forward under the ball with a jabbing motion. The ball is thus made to spin in the same way as when it is hit with the ‘overhand’ shot with cut. This is not at all an easy shot to produce: it is fatally easy to hit the ball down below the line, as everyone will find out who cares to make the experiment. But there are occasions when a winning stroke can be made by this means, and by this means only. Suppose you and your opponent are both on the step, and the ball comes to your right hand rather low off the bounce. If you aim to hole out in the box or nick it in the buttress, you will have to return the ball upwards onto the front wall and also slowly. In this case your opponent will intercept it easily, and you may give him a volley; but by using the method of applying cut just described you can hit much harder, for the spin will bring the ball down quickly again off the front wall. I do not advise any but the best players to attempt this stroke, but for them it is of great importance. In a really good game of Fives where all four players are equally matched there are precious few chances to score, and hardly any that are really easy. If then a method of nicking the ball from an ordinary return and from an unlikely position can be devised, a great deal has been achieved.

ON HITTING THE BALL

The first essential, as in all ball games, is to keep one’s eye on the ball; the second to attend to the position of the feet. Many strokes can be, and some should be, made with a stiff wrist, but all volleys (except, of course, those purely defensive volleys which are hit underhand), and all really hard shots are hit with a flexible wrist. No cut can be imparted to a ball that is hit overhand if it is hit with a stiff wrist. In good company the pace of the game will generally be very fast, and you will often have to make returns as best you can from any number of awkward positions; but when you have time to spare, attend to the footwork and the timing of the stroke. For a right-handed volley the left foot and shoulder should be in front and vice versa. Be careful not to snatch at the ball, particularly when volleying; it is more important to hit low than hard.

MATCH PLAY

Enter the Court with your hands as warm as possible. Do not hit wildly at the start of the game! Get your length first, and then begin to put on pressure. Four or five shots hit straight out of court or well below the line have a demoralising effect on your own and your partner’s play from which it is hard to recover. Study your opponents’ play carefully and find out their favourite strokes and their weak points. Always be thinking ahead of the immediate stroke, and try to dictate the run of the play as you want it. Above all never relax for a single moment, until the last point has been won: many, many sides have lost the match after leading 2-0. If your opponents are mighty hitters, try the effect of slowing down the game; if they play a canny game try to rush them off their feet. Things may often go badly, even when you are playing well. Don’t get rattled! Your opponents may have a run of luck and hit edge after edge. Remember that your turn may come soon: it probably will. In my experience the luck of hitting purely fortuitous edges levels itself up over a game of any length. Luck consists not in hitting edges, but in hitting them at vital moments, e.g. at Game Ball; that cannot happen often. If the play is very even try to keep something in hand, so that you may make a spurt at 8-all. It is very important to reach 10 first!

Finally, a five set match is a tremendous test of stamina, both of nerve and body, so you must be very fit, and you must never lose heart. I have known a game of Fives last as long as two hours and fifty minutes. Such a match is in my opinion more exhausting than any other form of sport in which I have ever indulged. The imagination boggles and the brain recoils before the sum total of times when in such a game a player is called upon to touch his toes, and thereafter immediately to hurl himself into the air. Such a feat could hardly be performed in cold blood.

SOME ADVICE FOR THE BEGINNER

It may be helpful to summarise a few of the points that have been mentioned:--

(1) Learn to serve well.

(2) Take every opportunity to strengthen your weaker hand.

(3) Realise the importance of foot work and keep your eye on the ball.

(4) Try always to return the ball as low as possible on the front wall.

(5) Unless you are reduced to getting the ball up at any cost, try to aim for an effective and accurate stroke.

(6) Take every opportunity to play with players better than yourself.

(7) Practise the more difficult strokes when you are playing in less expert company.